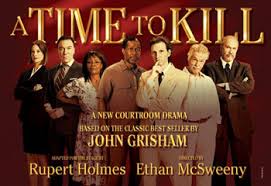

The closing a month ago of the Broadway stage version of John Grisham’s novel, A Time to Kill, as well as the recent wave of films starring the reconstituted Matthew McConaughey, bring to mind some strange correspondences between the dramatization of that novel and an iconic movie from the 1940s:

The closing a month ago of the Broadway stage version of John Grisham’s novel, A Time to Kill, as well as the recent wave of films starring the reconstituted Matthew McConaughey, bring to mind some strange correspondences between the dramatization of that novel and an iconic movie from the 1940s:

Those old liberal softies Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin, were probably grinning in paradise as they read accounts of the attempts to make a stage vehicle out of John Grisham’s entry in the “sensitive white man in Mississippi saves the Negro race” narrative sweepstakes, A Time to Kill. Maybe there is a heavenly version of Netflix and they even got a chance to stream the 1996 movie version, anticipating each echo.

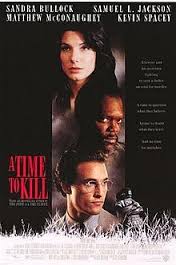

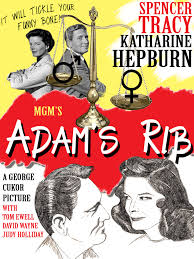

After all, the writers and producers of ATtK (both versions) simply took the premise, conflict, and climax from one of Gordon and Kanin’s finest comedies to build their own scripts. Give up? It’s Adam’s Rib, the 1949 classic starring Katherine Hepburn in the Matthew McConaughey role of liberal defender, Spenser Tracy in the role of the DA with political ambitions taken over by Kevin Spacey in ATtK, and Judy Holliday in the shooter’s role taken by Samuel Jackson in the film.

Those of you who are insomniacs will remember that in AR, Holliday shoots Tom Ewell who was cheating on her, Hepburn takes her case while film hubby Tracy is assigned to prosecute it, and in the film’s climax Hepburn delivers a clever summation that wins the day and the case. Along the way we learn that Holliday planned her assault and knew what she was doing, that Hepburn intends to plead her as temporarily insane, and that there is an issue at stake larger than the issues of fact in the case: the unequal treatment of women before the bar.

In ATtK, Jackson shoots two men who have raped and almost killed his 10-year old daughter, McConaughey takes the case although he is lined up against a spineless judge and a conniving DA, and in the film’s climax delivers a clever summation that wins the day and the case. Along the way we learn that Jackson planned his assault and

knew what he was doing, that McConaughey plans to plead him temporary insanity, and that there is an issue at stake larger than the issues of fact in the case: the unequal treatment of Blacks before the bar in Mississippi.

There are other fascinating little parallels, most of them attributable to conventions of film plotting: in both films the defense lawyer and spouse separate because of the stresses of the case; in both films a feckless and entertaining comic relief who drinks a lot provides companionship to the defense; in each film a brief romantic moment looms on the horizon but is rejected by the defense.

But the most fascinating parallel has the most interesting implications for the representation of how the law is portrayed in American popular culture. It involves a basic conflict in legal ethics: in any given case, may a lawyer place her belief in a cause over and above her client’s case. In AR, Hepburn comes to realize that she must find

a way to free her client. Originally, her interest was in the larger political implications of the case, which she saw as embodying the sexual double standard as it was applied in the law: no man, she knew, would go to jail for doing what her client had done. The case offered her an opportunity to showcase women’s inherent

constitutional right to all justice, however twisted it might be; if men could assault for love’s sake and go free, so could women. But although Hepburn’s cause could be served just as well, if not better by Holiday’s conviction, an argument by Tracy reminds her that as a lawyer, she cannot put a cause before the welfare of her client.

McConaughey’s problem in ATtK is identical to Hepburn’s and his position in the problem is similar but also different. There is a certain amount of bravado in both characters’ decisions to take the case, youthful in his and messianic in hers, and a certain affection for publicity in each’s early pursuit of their clients’ interests. But the over-investment in the cause Jackson represents is not McConaughey’s, despite the fact that he took the

case to expose the problem of justice for Blacks in Mississippi, but that of the NAACP and a local Black minister. Together, Jackson and McConaughey fend off an attempt by the NAACP to co-opt the case with its own lawyer, one who, it is hinted, would be willing to let Jackson get the chair if it suited the political moment.

Nevertheless, the cause has its own life and drives actions outside the courtroom that have effects on McConaughey’s efficiency in the case as riots and racial conflict as well as motives of revenge bring the KKK into town and into the case. When both sides have rested, McConaughey, as was Hepburn in her case, is far from a victory and he has no new ideas. It looks as though the cause will be served by Jackson’s conviction.

Hepburn’s summation is clever and blithe, until she turns to the narrative device she has fashioned to win the case for her. She abandons the insanity plea; she abandons the apotheosizing of women every bit the equal of men in public and private life. Instead, she asks the jury to listen again to the story of the spurned and

heartbroken spouse, the heartless lover, the straying marriage partner but this time, she insists, the jury must look closely at the defendant and at the victim and at his girlfriend and imagine them changed! Imagine them, she insists, as a heartless male home wrecker, a bored, straying wife, and a jealous husband with too much honor and a gun. As she does this, film magic turns Holliday into a middle-aged man, Ewell into a homely woman, the girlfriend into a handsome rake. The lesson is driven home and the jury acquits Holliday because they have seen her as a man in their mind’s eye, with a man’s prerogative of honor.

McConaughey’s summation is absent any ornamentation. He declares that he is abandoning his prepared summation to tell a simple story. He asks only that the members of the jury close their eyes while he does so, and that they listen closely. The jury complies and McConaughey tells a story of brutal rape and torture of a small girl

by two men, of their attempts then to hang her and of her body thrown from a bridge to a creek bed 30 feet below. Imagine all of this, he asks, and then, imagine the child white. The lesson is driven home and the jury acquits Jackson because they have seen him and his daughter as white, for one moment, and realized that they would have done exactly as he had done, had they been in his place.

I have no insider’s knowledge that the writers and producers of ATtK dug up an old print of AR and sketched their outline from there. There may be good reasons why issues of inequality before the law almost cry out for race and gender border-crossings, for exercises in the development of moral imagination. It is certainly the case in

both of these examples that the judge would have been quite justified in criticizing the jury for its failure to adhere to the points of law he had laid out for them. Both films, it must be noted, leave a close observer with the impression that a lot of legal work can go down the drain in a hurry if one lawyer shows up for closing arguments with a better narrative hook than the other has at hand. And this is despite the common legal wisdom that most

cases are won or lost in the opening statement, not in the summation, Johnny Cochran’s performance in the “O. J. Case” notwithstanding.

The films do part company, however, at the point of just how much ambiguity the law will be allowed to tolerate. In the 1949 film, Tracy is allowed to lecture Hepburn several times on the absolute solidity of the law as a response to human behavior. Assault is assault, whoever attempts it. In one of the longest denouements ever filmed, after he has lost the case Tracy surprises Hepburn from whom he has separated as she is fending off the advances of their

feckless neighbor. Pulling a pistol from his coat, Tracy pretends to be on the verge of homicide when Hepburn argues that he has no right, that no one has the right to take the law into his own hands. Tracy smiles, places the weapon in his own mouth and… bites off the barrel of his licorice-flavored .38 police special. Having fallen into his trap, Hepburn still refuses to apologize for having lured the jury into what was patently an act of jury nullification and the couple squabbles on to the end of the film until tax law reunites them. But the forces of case law win

over those of cause law rhetorically.

In ATTK, however, the denouement is a simple visit by McConaughey to Jackson’s house for a cookout. There is no insistence in the film that McConaughey’s appeal to the moral imagination of the jury, causing them to ignore the legal definitions given them that would determine Jackson’s sanity under the law, is in any way to be deplored or guarded against. The “Tracy” arguments from AR are given early in this film to Spacey, in whose character’s mouth the very word “justice” must sit like a cheap cigar, and the film never even bothers to answer him, except with the verdict of the climax. Even McConaughey’s wife, in a partial “Tracy” space, returns to him and forgives him for spending too much time on the case, absolving him and the verdict itself by telling him that he took the case because if their daughter had been the victim, she knows, he would have killed those men himself.

What has changed in sixty years? Have we come to accept that the law is not what Tracy saw it to be, a rock of surety in a sea of complex social relationships, but rather another narrative of our life, with its own aporia, its own conventions, its own highly-developed tolerance for ambiguity? Gender/race, case/cause, law/fact, story/story, options and choices all the way around? But did we believe, sixty years ago, that gender was a social construction? Do we believe now that race is so? Do the dramatists, stage or film, rightly assume we accept race/gender transgressions for the right cause? If the story is good enough? Or maybe it’s something else.

Maybe the mechanism of AR were appealing to the producers of ATkK because the films are really about the same thing, seen through the lens of the law, but still seen the same. Maybe the films are both about family, for one. Both defendants were on trial for acts they undertook in defense of family; the subplots of each were about the

families of the lawyers, at the end of each film the defendants are reunited with the loving members of their families, just as, in the denouements, the lawyers are reunited with their families. And here the differences are informative. The gap between Hepburn and Holliday, class, is larger than their gender affinity can bridge. After the trial, Holliday, et al, vanish from the screen and we are treated to another quarter hour of Tracy and Hepburn making up. But the gap of race between McConaughey and Jackson, so carefully limned by Jackson when he tells McConaughey that he wanted him for his lawyer because McConaughey was one of “them,” a white man, and a

racist by default, may be bridgeable, if the film has its way. When Jackson says McConaughey and he aren’t friends, don’t live in the same part of town, that their kids don’t play together, he challenges the fiction of equality even under a system of law. He impresses us with the fact that law is just one more story about how folks live, and maybe not the most accurate one. So he wants McConaughey because he figures McConaughey knows what kind of story a white man would want to hear to let Jackson go free. And he needs McConaughey as a lawyer because it has to be a story told within the conventions the law privileges.

Jackson has no illusions, about whites or about law; McConaughey has no illusions either, but neither has he any insight, until Jackson explains things to him. So, in the film’s final scene, when McConaughey, his wife, and his

daughter drive up to the cookout going on at Jackson’s house, they are clearly not invited guests. There is some momentary confusion, but they have brought some strawberry shortcake for the table and McConaughey says he brought his daughter so she could play with Jackson’s. Families, smiles all around; pull back, fade out.

Class insurmountable in 1949; race transposable in 1996/2013; families reconfigurable always. Class in 1996/2013? The dead rapists were white-trash morons. The film doesn’t even make a half-hearted gesture to them or their families. Family ties there lead only to the Klan, violence, and lawlessness. McConaughey is “U” to be sure,

blond, fit, handsome, married to a sorority girl. And McConaughey has legal class as well; he’s the protégé of a famous old civil rights activist whose practice he has taken over and whom he considers to be his father in every way but blood. Even the mystery girl of the picture is upper-class. She appears out of nowhere, a

third-year Harvard law student, a genius whose father is filthy rich. She has come because she heard about the case and wants to assist, without pay, of course, because, has she mentioned it, her father is famous and rich. Needless to say, she is beaten by the worthless surviving brother of one of Jackson’s victims.

In Hollywood, and in at least some instances on Broadway, social justice is a zero sum game. Poor woman defendant, rich woman lawyer. They meet on the relatively level playing field of the court, but not outside of it. Poor white trash or poor Black worker. Rich white folks can’t save them both. So these are really two/three versions of the same film, and they’re not that different, even with sixty years between them. Americans still cling to family and class and still love to tell stories about both, in the movies, on the stage, and in the courts.